Environment of the Central Coast

The Central Coast is in the heart of the world's largest coastal temperate rainforest termed the Great Bear Rainforest - a wet, wild place shaped by strong interactions between land and sea. Some key characteristics that make this area unique are described below.

|

Biogeoclimatic Zones

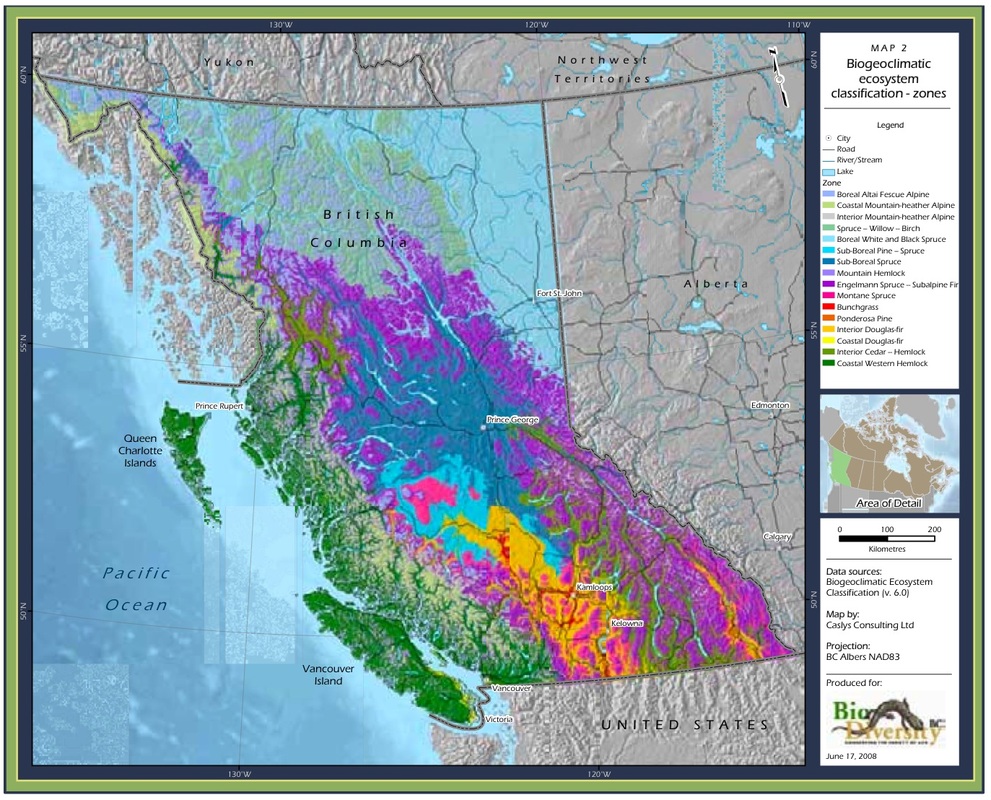

The Central Coast is a unique area of a very diverse province. BC's terrestrial landscape is home to great biological, geographical, and climatic variation; the intersection of these components is described by the Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification (BEC) system. This system was developed specifically for BC - it classifies areas of the province by biogeoclimatic zones, which essentially are "broad geographic areas sharing similar climate and vegetation" (Biodiversity BC, 2007). The map at right depicts the results of this classification system (click to expand). It is a visual representation of BC's diverse landscape, and for the purposes of this site it helps illustrate the uniqueness of the coast. The Central Coast of BC is largely situated in the Coastal Western Hemlock zone. |

The biogeoclimatic zones of BC, from biodiversitybc.org. A more detailed map is available here (warning - large file size). |

Geology, winds, and currents

BC's Central Coast has been shaped by a number of complex processes. The BC coast stretches along the junctures of four different tectonic plates - the Pacific, the North America, the Juan de Fuca, and the Explorer Plates. Over millions of years the interactions of these plates, as well as other geological processes, have formed a complex and diverse terrain. Going westward from the Coast Mountains the terrain drops towards sea level, where the mainland breaks up into hundreds of inlets, fjords, and islands.

Prevailing winds from the west bring warm, wet air from the Pacific Ocean to land, where it hits the Coast Mountains, cools and falls as precipitation - a lot of precipitation. Henderson Lake on Vancouver Island gets the most rain of anywhere in North America, at an average of 6650 mm each year.

BC's Central Coast has been shaped by a number of complex processes. The BC coast stretches along the junctures of four different tectonic plates - the Pacific, the North America, the Juan de Fuca, and the Explorer Plates. Over millions of years the interactions of these plates, as well as other geological processes, have formed a complex and diverse terrain. Going westward from the Coast Mountains the terrain drops towards sea level, where the mainland breaks up into hundreds of inlets, fjords, and islands.

Prevailing winds from the west bring warm, wet air from the Pacific Ocean to land, where it hits the Coast Mountains, cools and falls as precipitation - a lot of precipitation. Henderson Lake on Vancouver Island gets the most rain of anywhere in North America, at an average of 6650 mm each year.

The corresponding surface currents that flow eastward from the Pacific Ocean encounter land near the Central Coast, and split into the Alaska and California currents. This split means a large part of BC's coast is in a transition zone between coastal upwelling and coastal downwelling - two processes that have very different effects on the temperature and nutrient composition of coastal waters. This transition zone shifts a bit depending on climate fluctuations and seasons.

The Central Coast is generally near the edge of the transition zone and the upwelling zone. Coastal upwelling brings nutrients to the surface of the water; these nutrients form the basis of complex marine and marine-terrestrial food webs, while the variation in habitat conditions caused by the transition zone cultivates variation in marine life. Click here for more information on these processes.

The Central Coast is generally near the edge of the transition zone and the upwelling zone. Coastal upwelling brings nutrients to the surface of the water; these nutrients form the basis of complex marine and marine-terrestrial food webs, while the variation in habitat conditions caused by the transition zone cultivates variation in marine life. Click here for more information on these processes.

Interactions between land and sea

While large-scale land-sea interactions have shaped the climate and topography of BC's coast, smaller-scale biotic and abiotic processes also interweave the land and sea. The tides and currents work away at shorelines in different ways depending on variables such as wave energy, shoreline exposure, and location, so that some shores are rocky and some sandy, some have much marine detritus washed ashore and others have less, some shore slope gently into the sea and some plummet into the water. The way the sea shapes the shoreline affects which species inhabit intertidal and near-shore areas.

Marine nutrients washed ashore are consumed by shoreline plants, scavengers, and detritovores, and from there work their way up the food chain. When washed ashore, Pacific herring eggs provide nutrients for terrestrial species including black bears, wolves, birds, and small mammals. These marine-based nutrients are transported inland via waste from terrestrial species, where they fertilize forest habitats.

While large-scale land-sea interactions have shaped the climate and topography of BC's coast, smaller-scale biotic and abiotic processes also interweave the land and sea. The tides and currents work away at shorelines in different ways depending on variables such as wave energy, shoreline exposure, and location, so that some shores are rocky and some sandy, some have much marine detritus washed ashore and others have less, some shore slope gently into the sea and some plummet into the water. The way the sea shapes the shoreline affects which species inhabit intertidal and near-shore areas.

Marine nutrients washed ashore are consumed by shoreline plants, scavengers, and detritovores, and from there work their way up the food chain. When washed ashore, Pacific herring eggs provide nutrients for terrestrial species including black bears, wolves, birds, and small mammals. These marine-based nutrients are transported inland via waste from terrestrial species, where they fertilize forest habitats.

Chum salmon. Photo by Morgan Hocking.

Chum salmon. Photo by Morgan Hocking.

The annual migration of Pacific salmon is perhaps the best-known example of such marine-terrestrial interactions. When Pacific salmon return to their freshwater spawning grounds they bring with them important marine-derived nutrients. As bears, wolves, gulls, and other scavengers feed on the spawning salmon and their carcasses, the salmon remains as well as waste from these animals are transported into the surrounding forest habitat, where they provide nutrients for a multitude of other species. This includes the tall trees of the rainforest: marine-derived nitrogen has been found in trees surrounding salmon spawning grounds. As some plant species grow better in nitrogen-rich soils while others prefer nitrogen-poor soils, this annual pulse of marine-derived nitrogen impacts which plant species grow near salmon-bearing streams and lakes. The interesting result of this is that plant diversity might decrease within specific areas as select species thrive in nitrogen-rich conditions, but this can result in wider diversity between habitats.

The implications of this annual pulse of marine-derived nutrients for coastal plants and animals are the subject of research by Dr. Tom Reimchen and his lab team at the University of Victoria, in an on-going project known as 'The Salmon Forest.' See the Reimchen Lab Salmon Forest Project page for further information on the project and its publications. Links to some of these publications are provided in the Articles and Publications section of our Media and Links page. Also check out this David Suzuki Foundation article that neatly summarizes many of the salmon forest interactions that have been explored so far.

The implications of this annual pulse of marine-derived nutrients for coastal plants and animals are the subject of research by Dr. Tom Reimchen and his lab team at the University of Victoria, in an on-going project known as 'The Salmon Forest.' See the Reimchen Lab Salmon Forest Project page for further information on the project and its publications. Links to some of these publications are provided in the Articles and Publications section of our Media and Links page. Also check out this David Suzuki Foundation article that neatly summarizes many of the salmon forest interactions that have been explored so far.

Biodiversity

The result of the above factors is a complex mosaic of diverse marine and terrestrial habitats. Such high habitat diversity gives rise to high biological diversity. A large proportion of this diversity consists of microscopic, minuscule, and inconspicuous species, on which the larger, more obvious, and more charismatic species - and indeed the whole ecosystem - rely. This site focuses on these larger species as they tend to be of more interest to the general public, but it is important to note that they compose only a small portion of the region's biodiversity.

The result of the above factors is a complex mosaic of diverse marine and terrestrial habitats. Such high habitat diversity gives rise to high biological diversity. A large proportion of this diversity consists of microscopic, minuscule, and inconspicuous species, on which the larger, more obvious, and more charismatic species - and indeed the whole ecosystem - rely. This site focuses on these larger species as they tend to be of more interest to the general public, but it is important to note that they compose only a small portion of the region's biodiversity.

References

(2007). 23 Major Findings: BC Is Special. Biodiversity BC. Accessed 17/09/2103.

(2012). A Global Treasure. Take It Taller. Rainforest Solutions Project. Accessed 17/09/2013.

Government of Canada. (2009). Discover the Rainforest. Pacific Rim National Park Reserve of Canada. Parks Canada. Accessed 17/09/2013.

How BEC Works. Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification Program. Research Branch, Forestry Service British Columbia. Accessed 17/09/2013.

Global Ocean Currents. Watershed Protection. Capital Regional District, Victoria, BC. Accessed 17/09/2013.

(2007). 23 Major Findings: BC Is Special. Biodiversity BC. Accessed 17/09/2103.

(2012). A Global Treasure. Take It Taller. Rainforest Solutions Project. Accessed 17/09/2013.

Government of Canada. (2009). Discover the Rainforest. Pacific Rim National Park Reserve of Canada. Parks Canada. Accessed 17/09/2013.

How BEC Works. Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification Program. Research Branch, Forestry Service British Columbia. Accessed 17/09/2013.

Global Ocean Currents. Watershed Protection. Capital Regional District, Victoria, BC. Accessed 17/09/2013.